Legislation

Repatriation of cultural material is governed by legislation, much of which is embedded in centuries of colonial practice and policy. Over time these laws have built upon each other, founded in largely European understandings of ownership and warfare, culminating in the current state of repatriation legislation and policy within museums. This chapter will provide an overview of relevant legislation, from early Common Law and colonial-era governance, to twenty-first century international legislation. The purpose of this overview is to contextualise the issues in museum policy that will be mitigated by the outline of informed museum practice through this research.

Early British Legislation

Current repatriation issues in British and Irish museums have their roots in early legislation which laid the foundation upon which museum collections were built. The oldest and most comprehensive of this legislation is Treasure Trove Common Law, a conglomeration of decisions on individual cases, has its origins in early Roman Law which held that discovered treasure was the property of the State, including England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland (Bland et al. 2017, 108; Blanchet and Grueber 1902, 148). Treasure Trove was likely first used as a legal concept as early as the eleventh century (Dawson 2023, 6). The later British Common Law defined ‘treasure trove’ as where any ‘gold or silver, in coin, plate, or bullion is found concealed in a house, or in the earth or other private place, the owner thereof being unknown’, and established that any treasure uncovered was the property of the British monarchy (Emden 1929, 90). While the definition requires that the finds covered under treasure trove be deliberately buried in the ground, the law set the standards for ownership of precious cultural objects by the British monarchy (Bland et al. 2017, 108).

The Common Law concretely defines treasure and stipulates actions to be taken in the event of uncovering the material, yet the question of how far this jurisdiction extends in time and place remains. It is not made explicitly clear in the case law, however it is possible that the British crown legally owned all treasure concealed underground, even prior to the finding of such material (Emden 1929, 95). Such a precedent of cultural material inherently belonging to the crown, whether they are currently in possession of it or not may inform on the realities of the landscape of ownership of cultural material when it comes to British colonies. This would set the precedent for all material of value on land claimed by the British government inherently being the property of the crown.

The usefulness of this common law for the British monarchy or the British government has been questioned by antiquarians and archaeologists including Flinders Petrie, who argued that the crown gained little monetarily from acquiring small amounts of treasure over time (Petrie 1904, 183). However, it could be said that what they gained in intrinsic cultural wealth outweighs monetary value. The functionality of the law is more clear when discussing the benefit to Britain as a whole, as eventually the finds reported due to Treasure Trove Common Law and acquired by the Crown created a vast national collection (Petrie 1904, 185). Despite the benefits of creating a national collection, law scholars certainly did find flaws with Treasure Trove. William Martin and Godfrey Lushington argued in their 1908 commentary ‘The Law of Treasure Trove’, that the removal of objects from their original contexts is detrimental to archaeological study (Martin and Lushington 1908, 353). The issue of the removal of cultural material whether archaeological or ‘ethnographic’ in nature, from its provenance is a catalyst for pro-repatriation arguments today. A predecessor to more recent issues of looting and removal of cultural material from British colonies for display, Treasure Trove Common Law set a precedent for the control over cultural material being in a centralised location separate from the original provenience. While this law was primarily meant to apply to archaeological material of gold or silver found within the bounds of Britain and Ireland, the precedent extended far beyond those reaches.

Following the standard set by Treasure Trove is the British Museum Act of 1753. While Treasure Trove created the paradigm for ownership of ‘treasure’ by the crown, the British Museum Act went further in creating the concept of national ownership over objects of cultural importance in Britain (United Kingdom 1753). The Act sets the collection of Hans Sloane as the basis of a national collection in what is now the British Museum, the Natural History Museum, London, and the British Library.

Colonial Era Legislaiton

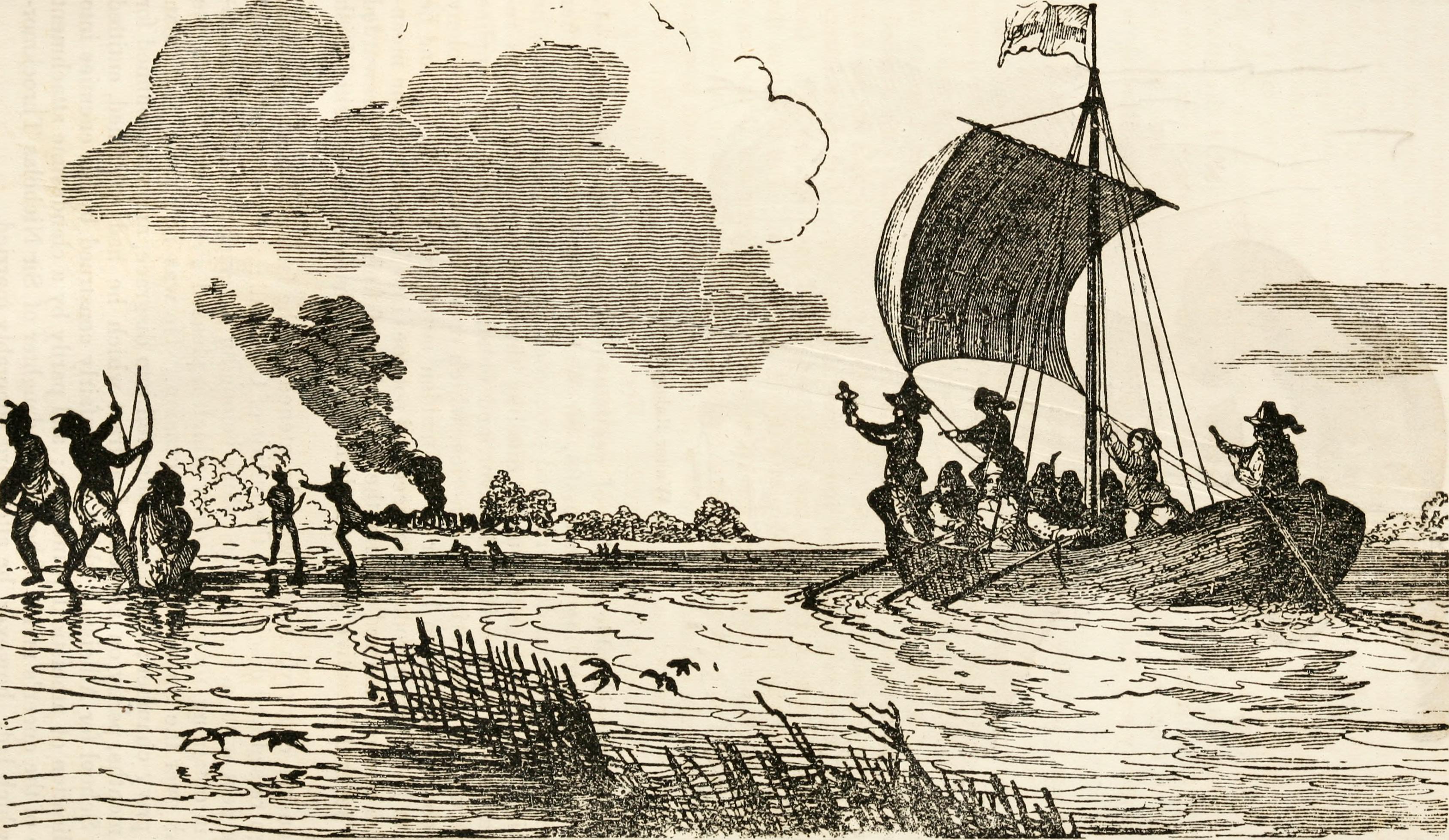

Colonisation itself has been justified with the idea that colonising forces are benefitting Indigenous peoples by disregarding existing legal systems and imposing ‘superior’ European legalities in conquered territory (Castles 1963, 1). Economic factors too influenced the process of colonisation, as scholars have also argued that capitalist beliefs, such as Lockean liberalism have built a foundation upon which colonisation could thrive (McBride 2016, 10). The idea of an inherent right to ownership paved way for appropriation of land and material in the custodianship of Indigenous peoples. It was this desire to appropriate land and resources that led to legislative measures instituted by force across British colonies (McBride 2016, 11). Through this practice of legislating colonies based on the beliefs of the colonisers, Indigenous populations were criminalised and infantilised, providing colonising forces with further access to resources, and full jurisdiction over cultural heritage in many cases (McBride 2016, 28). Ultimately, the invading power simultaneously provides themselves with unchecked access to cultural material and justifies the imposed legislation with the belief of superiority over ‘primitive’ Indigenous peoples (Bachmann and Frost 2012, 310).

In the early stages of British colonisation, legislation was not always well documented, if in place at all. This is the case for early legislation regulating the looting of cultural material, or the removal of such material from that colony. Despite this lack of legislation or lack of documented policy, the legislative frameworks of colonies help to frame the context of looting, and so will be discussed in this section. In order to understand looting in a colonial context, it is crucial to understand notions of ownership under law, and the way that colonisation, alongside its legal framework, paved the way for acquisition of antiquities. If it were not for a legislative framework which set out land and all property as the inherent right of the colonising force, acquisition would not have been possible to the extent that it was carried out. Treasure Trove Common Law and its successors contextualise the basic belief system upon which later legislation was founded. Foundational understandings of ways of being differ greatly between British viewpoints and Indigenous ones, yet with British colonisation of Indigenous peoples came the imposition of British belief systems through legislation and policy. It did sometimes occur that pre-existing legal systems which were deemed ‘civilised’ were kept in place until invading forces saw a necessity for imposing new rule of law (Castles 1963, 1). However this was often not the case, as Indigenous peoples and the legal systems they created were almost always viewed as primitive. Passing of legislation by invading British powers served to impose Western belief systems onto the lives of Indigenous people who may not have viewed cultural material as something to be owned. Not only would this legislation have been incongruent with much of existing Indigenous law and understanding in many regions of the British Empire, but it would also have served to widen the disparity between colonised and coloniser.

The unequal power dynamic of colonised and coloniser was compounded by a lack of access to and understanding of legislation due to low English literacy rates. Literacy rates in British colonies were on average lower than their French counterparts, due to a focus on educating only a small elite class, rather than the masses (Cooray 2009, 8). For instance, in British India thirty percent of the elite Brahman class could read English, while only two percent of all other castes combined could. Those who were able to read the legislation in English and work within the legislative system inherited more power and knowledge under the colonial system than those who did not understand English, and who did not have a Western belief system necessary to contextualise colonial legislation.

Colonisation in Ireland

Colonial policy in Ireland in many ways served as a dress rehearsal for later exploits of the Empire, providing a step-by-step manual for colonisation of other Indigenous people (Rahman, Clarke and Byrne 2017, 15). This early imperialism was largely based in resource extraction, and capitalist ideals which originated in the English countryside and were transported to British colonies, the first of which being Ireland (Jones 189). The capitalist aim of extracting resources from colonies paved the way for the extraction of cultural material as well. Ireland was no stranger to removal of cultural wealth by the passing of the British Museum Act in 1753. As part of the ‘United Kingdom’ for much of Britain’s colonial era, Ireland too was under the jurisdiction of Treasure Trove Common Law. As such, Irish ‘treasure’’ was determined to be rightfully owned by the British crown, and the Royal Irish Academy (RIA) was granted acquisition of Treasure Trove objects in Ireland from 1860 (Costello 1997, 157). One such case in which this legislation was put into practice was that of the Broighter Hoard.

Discovered near Derry by farmers in 1896, the hoard of fine gold object was taken from the site and sold to the British Museum by the antiquarian collector dealer Robert Day for £600 (Warner 1999, 69). Day had neglected to go through the proper channels for reporting finds of treasure to the government, which would have allowed the Royal Irish Academy, under the jurisdiction of the British monarchy, to acquire the objects. As the hoard had been acquired by the British Museum, deaccessioning of the material was prohibited except by Act of Parliament (Warner 1999, 71). Irish Solicitor-General Edward Carson argued that the hoard was Treasure Trove and therefore belonged to the British crown (Warner 1999, 72). The British Museum’s counterargument consisted of broad generalisations with the ultimate point that the objects were of too fine a quality to have been created by Indigenous Irish craftspeople, and therefore did not belong on Irish soil. Ultimately the hoard was deemed to fall under the jurisdiction of Treasure Trove Common Law, though the process of the British Museum returning the objects was not so simple (Ireland 2014, 86–87). A Bill was presented to Parliament ‘to enable the transfer of certain Irish Antiquities from the British Museum to the National Museum, Dublin’ in 1898 which would have allowed for the returns as a special consideration for Irish material in the British Museum, however the Bill was not subsequently passed due to direct intervention by the ‘friends of the British Museum’ (Ireland 2014, 87). What followed was a court case which saw the British Museum and the RIA attempting assert claims over the finds (Ireland 2014, 95). The conclusion to the case came when the finds were found to be Treasure Trove and Edward VII ordered the objects returned to Ireland (Warner 1999, 74; Ireland 2014, 103). While the decision in this case benefitted Irish national cultural collections, this was certainly not the norm.

Many Irish antiquities were removed from Irish soil and taken to Britain. Often it seems to have been a lack of legislation which allowed for such removal. Antiquarians such as Thomas Lalor Cooke collected invaluable Irish antiquities such as the Bearnán Chúláin bell-shrine which was part of a large private collection later removed from Ireland and sold to the British Museum in 1854 (Murray 2016, 25). Anglo-Irish antiquarian and dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, Henry Richard Dawson, also amassed a large collection of antiquities including a portion of the Late Bronze Age Dowris Hoard which was later purchased by the British Museum (Dawson 2023, 101, 123). Legislation did not set out restrictions on such removals. Other collectors such as Pitt Rivers and Thomas Tobin also acquired antiquities though private sales that were not regulated by Treasure Trove Legislation. Many of these antiquities were ultimately removed from Ireland and donated or sold to museums in Britain, such as the South Kensington Museum, which is now the V&A, the British Museum, or Oxford University, at what is now the Pitt Rivers Museum (The British Museum 2023c, 2023b; Pitt Rivers Museum 2023). Despite the Treasure Trove legislation that saved the Broighter hoard for Ireland, many antiquities were looted or otherwise removed from their contexts.